Book Review: “The Road Before Me Weeps” – Nick Thorpe

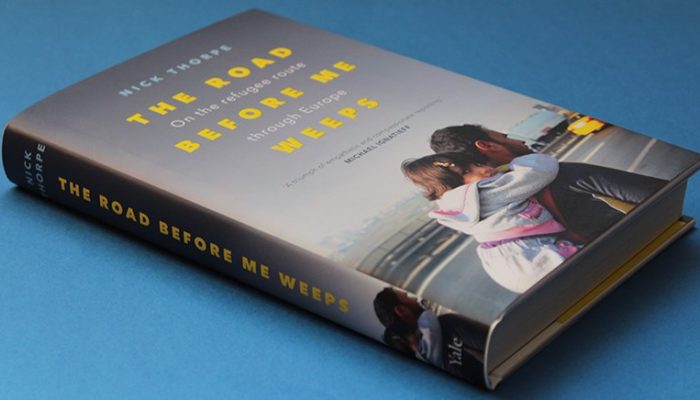

“The Road Before Me Weeps: on the refugee route through Europe”, Nick Thorpe, Yale University Press, 2019, 332 pages

As a long-time BBC correspondent in Budapest, Nick Thorpe is well-placed to write up a road trip with the 3.7 million refugees who fled to Europe during 2014-2018. The large and sudden movements of people made the EU’S Schengen and Dublin entry procedures unmanageable to countries on the EU’s eastern and southern borders, which right wing nationalists and autocrats used for political advantage. A strong grasp of European history and politics enables him to explain the EU’s inadequate ‘architecture’ of response. Focus is placed on the three major players of Prime Minister Orban of Hungary, President Erdogan of Turkey, and Chancellor Merkel of Germany, with the latter consistently adopting a welcoming posture. She and Orban became the two poles of the debate about Europe’s cultural, religious and demographic future.

The book begins in 2014 with significant numbers of Kosovo Albanians leaving economic distress, Syrian and Iraqi refugees fleeing to Europe, the Charlie Hebdo terror attack in Paris, attacks on migrant hostels, and anti-Islam mobilisations by Pegida (“Patriotic Europeans against the Islamization of the West”) in Germany. Fidesz, the declining political party in Hungary led by Victor Orban, took the opportunity to revive old ideas of a Christian defence against Muslim invasion, by fortifying the border with Serbia and making illegal entry a criminal offence. At first, the contrary view was expressed by Austria, Germany, Sweden, the Netherlands, Scandinavia and to a lesser extent, France. Theirs was for both refugee protection and an aspiration for Europe to be a “safe haven” with legal pathways for “genuine refugees”, defined as Syrians, Eritreans and northern Iraqis.

Despite Orban’s opposition, the Budapest city council supported the newcomers. Much practical support to supply food, clothing and shelter came from thousands of volunteers who were unhappy with the inadequate response from state and church organisations. They set up groups such as Migration Aid, Kalunba and Migration Solidarity in Szeged. Merkel spoke out and became their hero, with positive comments about accepting Syrian refugees, that Islam was part of Europe, and humanitarian principles were important. In Hungary, this had only temporary effect: Orban’s negativity seems to have reversed public opinion from 2/3 supporting refugees in Sept 2015 to 2/3 against, one year later. Yet the xenophobia drumbeat can tire: his referendum for a No to resettlement quotas got only a 1/3 turnout, almost all endorsing his proposition. “The Hungarians are more European than their government” said the Luxembourg Foreign Minister.

Without resiling from previous large admissions, after Germany’s Sept 2017 election Merkel accepted a reduction in asylum seekers to a level close to the actual number of applicants. She said that the lack of preparation and explanation to other countries was the reason for the disputes between EU leaders. By 2018 the flow was much reduced, and Thorpe sees the EU financing deals with Turkey and Libya as largely effective in that respect, partly by boosting their economies but also by domestic containment of their population. There are too many twists and turns in the story to record here, but migration numbers were at a 5 year low by Jan 2019.

The horrific results of people smuggling – drownings and mass asphyxiation in lorries– led to debates on how to respond. What are the ethics and efficacy of different approaches? The unfairness of cruel treatment is that it is more likely to deter those with economic motivations, but not those who have no choice due to political or safety problems. And many deportees will just try again, as he documents. Perverse incentives were everywhere. Reducing legal pathways in favour of fences was found to force people into the hands of smugglers. It was also not a deterrent, but a magnet: a ‘rush to the exit’. Maritime obligations to rescue those stranded at sea increased smugglers’ use of unsafe boats to trigger rescue, and guarantee entry to both refugees and non-refugees.

Thorpe’s estimate is that 2 million people paid 8-10 billion Euros to people smugglers – four or five times the amount spent by governments on walls and surveillance equipment. He could have added the 6 billion Euros paid by the EU to Turkey to stop the exodus, which still left the most dangerous route open – across the Mediterranean. What an economic boost to flagging economies if that money had been spent in destination countries by migrants.

Another strength of the book is his detailed reports of many encounters with migrants, refugees and locals, NGOs, volunteers and smugglers, politicians and their operatives. The phrase “mixed migration” recognises that there are some imposters amongst the refugees, and Thorpe doesn’t sanitise the full range of stories he hears. The cases detailed here are arguments for why the “complementary” reasons for protection under the Refugee Convention need to include contemporary realities. Reasons for flight incapable of local redress might be child custody disputes, sexual or family violence, extortion, rampant crime, gang violence, bombing, terror, political or economic collapse, sickness or hunger. My conclusion is that the binary debate about economic migrants versus refugees is verbal junk, because failures of domestic politics and institutions have increasingly brought about hostile and unliveable milieus. Must people wait for these events to personally affect them before they are sanctioned to leave? At the recent Kaldor Centre Annual Conference, Hillary Evans Cameron presented a strong case for taking the asylum applicant’s side most of the time.

Yet post-conflict repatriation must not be abandoned as a goal, where possible. Many of the Syrian newcomers were educated middle class people, and Thorpe reminds us of the consequences of Syria’s loss to Europe of half its university educated and a quarter of its completed secondary educated: an educational regression of the workforce which will set its economy back decades, and undermine future success. And how effective can institutions be renovated without the input of those who had to leave in order to survive?

While his road trip finishes at the end of 2017, the long term status for many refugees and migrants is still unresolved, with great dangers now and ahead. His experience and knowledge qualifies him to sketch out a sustainable policy response (at June 2018), based on sharing the burden between states, controlling the inward flow with less self-selection, and putting newcomers to work and school. More recently, there are signs of innovation and learning in Latin America, from communities of practice in Europe, and private sponsorship in Canada, which frames its community sponsorship in the language of local hospitality, rather than universal human rights. The Australian government is interested in the latter, often seen as the “gold standard” for successful resettlement. But it’s yet to be seen whether our government is only interested in externalising the cost, rather than adding to resettlement.

Kevin Bain reviews refugee books at Independent Australia, and has compiled a Reading Guide for Mornington Peninsula Human Rights Group.