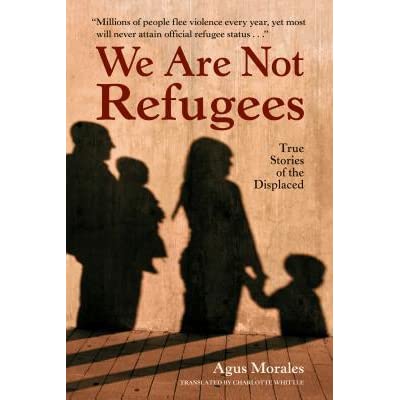

Book Review: “We are not Refugees: True Stories of the Displaced” – Agus Morales

“We Are Not Refugees: True Stories of the Displaced”, Agus Morales, (Translator Charlotte Whittle), Imagine Books, Watertown, USA, 2019, 271 pages

For about ten years to the end of 2018, the Spanish journalist Agus Morales covered the trail of those on the move in a number of countries in Africa, Central America, Europe, the Middle East and South Asia. He focuses here on ‘internally displaced people’ (IDPs in the jargon). IDPs are basically people without an entitlement to Refugee Convention support, because they have not fled outside their nation’s borders. In fact, of the 68 million ‘refugees’ (one percent of global population), only a third are outside their national borders. Since the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 more than 40 countries have built barriers of one type or another.

According to Morales, the official UN figures do not include those Central Americans fleeing to the US to escape gang violence, as the UN considers them to be migrants not refugees. There are also the Tibetans, provided with sanctuary by India for decades, who have never seen themselves as refugees. Their parliament in exile seems to be focused on cultural rites and regulations for their community, and there is an interesting dialogue reproduced here with Tibetan leaders explaining their fifty year exile. Other countries hosting or producing IDPs which are looked at are Jordan, South Sudan, Mexico, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Democratic Republic of Congo, Libya and Syria.

The definitions are not just about labeling semantics, or the jurisdictions for resolution – the relative proportions may help to understand the issues and point to solutions. For instance, people remaining close to their place of origin or in contiguous countries may show a motivation for return, although continuation of the conflict might bring second thoughts. (The reason for the Syrian exodus from Turkey to Europe in 2015 is a matter of debate. Morales says many felt that there was no end in sight to the war, Paul Collier believes families ran out of money because it was illegal to work until 2016, and there are a range of other possible reasons.)

The decision to stay or move is relevant to the IDPs because movement attracts attention from outsiders with influence, staying put does not. He tells us that since 2002, the number of IDPs in sub-Saharan Africa has remained stable, at around twelve million. Instead of their long period of detention leading to more knowledge about them and attention to solutions, the opposite has happened. Most IDPs live outside long-term camps, but both groups will stay for generations. IDPs waste away quietly, and leave this legacy to their children in a macabre rendition of “the poor will always be with us.”

There can be a status aspect operating with self-identification. Morales interviews middle class Syrians who tell him that refugees are the poor and the dispossessed, i.e. not them. Unlike people from Afghanistan, Somalia, Sudan and the Congo, these Syrians were not seeking food and accommodation. Many had means and a sense of agency, not wanting to be controlled by state officials and NGOs working from a blueprint. He tells of camps in Greece and the Balkans in 2015 with long queues to charge cell phones, while medical centres were almost deserted. Wifi opportunities were seized because these were people in motion, seeking communication and orientation, not nutritional support or protection from violence.

Morales is critical of unnamed NGOs and political parties whose pity and condescension reflected a sense of righteousness, rather than responding to the refugees’ aspirations, their dignity and human rights. He reminds us that many don’t identify as refugees, but as people with the same behaviours and values common elsewhere, but caught up in an unfortunate situation of diminished power. We should therefore reduce the tendency to judge from the outside, because “fleeing from a war doesn’t make you a better person, but feeling rejected can turn you into a worse one.”

His conversational style and personal stories will be attractive to readers seeking rich content about the motivations and dilemmas facing those on the move.

Kevin Bain reviews refugee books at Independent Australia, and has compiled a Reading Guide for Mornington Peninsula Human Rights Group.