Listening to child refugees and asylum seekers in Australia-what matters most

Background

In 1992, Australia adopted a policy of mandatory detention of people arriving in the country without a valid visa. This policy was targeted towards asylum seekers, and over time policies became increasingly punitive with the aim of deterring people from arriving through channels described by successive governments as ‘illegal’. Those policies have been rightly described as cruel and relentless (Magherita Matera et al., 2023). The narratives surrounding them and the use of the language of ‘illegals’ have created long-lasting, deleterious impacts for people seeking asylum. It has also created stigma for some people who have been granted refugee status.

In 2023, the Review of the Migration System (Parkinson et al, 2023), called for a new approach that focuses on building social inclusion and ‘a community of Australians.’ The Refugee and Humanitarian Entrant Settlement and Integration Outcomes Framework, released in October 2023, sets out a vision for Australia’s approach to refugee and humanitarian settlement. While not changing Australia’s approach to people seeking asylum the Framework aims to ensure that people who resettle in Australia feel belonging, safety and security. Since 2022, the language of belonging, inclusion and community-building has entered the Government’s narrative around refugee settlement, if not people who are asylum-seeking.

While past Australian policies towards, both people seeking asylum and resettlement of refugees, has received widespread attention, and the impact of such policies on children has been widely criticised, there is little, if any, research conducted with children to understand their experience of resettling in Australia and building a life as a refugee or people seeking asylum. As Australia seeks to place greater emphasis on ensuring refugees feel they belong, understanding children’s views and experiences is critical.

As part of a broader program of research, More for Children is designed to understand children’s experiences of growing up in contexts of poverty and financial disadvantage. Researchers from The Children’s Policy Centre at The Australian National University spoke with 15 children from Syrian and Iraqi Arabic-speaking and Afghani Hazaragi and Dari-speaking ethnic backgrounds who are either refugees or are seeking asylum. We used a child-centred, rights-based methodology and a range of participatory methods to support children in sharing their experiences and to develop a child standpoint on seeking asylum and building a life as a refugee in Australia. From listening to these children, we heard about issues of belonging, inclusion and exclusion, and trauma that shape children’s experiences; we also heard about the factors that support and hinder the efforts of children and their families to rebuild their lives.

We used the MOR for Children Framework, designed as a child-centred approach to understanding and responding to how children experience life in Australia across three dimensions of the material basics, opportunity, and relationships. The MOR Framework was developed to understand, assess and respond to child poverty – and to put children at the centre. Currently, 1 in 6 children in Australia are living in income poverty (Davidson et al., 2023), a statistic which is confronting for a wealthy country. While the statistics are important, our work is founded on the belief that behind every figure, is a story that deserves to be heard. The MOR Framework identifies how children from refugee backgrounds and those children who have sought protection onshore experience deprivation across each of the three dimensions.

We argue that child-centred approaches need to be embedded in policies towards people seeking asylum and refugees to ensure that children’s human rights are protected, and their relational and material well-being is secured.

Fig. 1 MOR Framework

Material:

Material deprivation is at the core of poverty (Lister, 2004), and many children we spoke with described the experiences that occurred when income is lacking, meaning there is often only adequate income for the essentials. Our research has shown that too many children in Australia deal with housing insecurity, food insecurity, and worry over their families’ financial income. However, for the children we spoke with from refugee and asylum-seeking backgrounds, this is exacerbated by the trauma they often face prior to their arrival. Often, they and their families are without the means to secure employment or seek help due to their visa status, affecting their ability to lead a life with an adequate standard of living. This was the reality for two boys we spoke with in regional Victoria, aged 10 and 12.

“My dad is trying to fix [the roof], like two months ago it fell in…there’s like cardboard there but it’s just a very bad smell, you know the filling they put in the roof for when it rains it smells. My brother sleeps on the couch, and I sleep on the ground on a mattress. My little sister sleeps next to me” (Boy, 12 years)

Opportunity:

While sufficient income is essential for an adequate standard of living, so too are the opportunities that allow children to enjoy life now and into the future. For the boys who described their living situation, a fun outlet was all they wanted. When asked what would make life better, they simply drew a poster asking to play soccer saying it was the only thing they wanted, but they could not afford to join the team, highlighting the lack of opportunities available to them when material security is lacking.

Play and leisure are a child’s right, as stated in Article 31 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989), of which many are being denied, but a right that is more frequently recognised is the right to education. Education is often equated with opportunity for children. Yet, for these children school is difficult. One boy expressed his frustration as he said:

“It’s [school] difficult and no one helps me” (Boy, 11 years)

The children spoke of the pressure they feel to do well in school, to become school captain, with the hope of receiving a scholarship. This pressure was confounded by the responsibility of their home lives as many of the children acted as interpreters for their parents saying that it was easier for them to learn English as they went to school, while their parents did not often have the opportunity to learn English.

While the pressures associated with school were difficult for the children, so too were the relationships they navigated in school. This was portrayed powerfully by one young girl as she said:

‘‘They [children at school] say our names differently like just to make fun of us (when asked what makes life tough) … It’s easier to be in your country ‘cause things like making fun of you ‘cause of features don’t happen” (Girl, 12 years)

Relational

Friendships were of great importance in the children’s lives, but family relations were central in the accounts shared. The relationships they shared with their families were powerful in the love that they shared but painful in their stories of separation and worry they spoke about. One boy when asked what would make life better, drew a poster of a broken heart and his sister on a plane. He said:

“Miss, do you know why I am sad, ‘cause my big sister is in Jordan” (Boy, 10 years)

The love and care the children had for the families was often expressed in the worry they had for their health, safety and wellbeing. This was expressed by one boy, aged 12, who said his parents are “struggling, for 10 years now” as he spoke of the health struggles they faced.

“My dad can’t work; he has a bad back. He’s sick, he has diabetes, and he has this kind of condition where he just starts itching and he has to put this cream on and my mum she has stress and just some random time blood starts coming out of her nose. It happens most days and my dad has kidney stones” (Boy, 12 years)

Strong familial relations stand as a strong protective factor in the resettlement experiences of refugee and asylum seekers (Pielock et al., 2016; Treanor, 2020). However, it also reaps pain and sadness in the lives of the children when they are separated from their families with no hope of reunification due to precarity around their visa status.

Where do we go/what do we do:

As we note above, Australia is in the process of rethinking its approach to migration broadly, and specifically regarding its humanitarian program. This creates the potential to design an approach that is genuinely inclusive of children and ensures they feel they truly belong.

The 2023 national budget also saw some positive steps, such as additional funding to support visa processing (Martin, 2023), however, much of the policy decisions were centred around boosting the economy through education and skills training. Children were completely absent from any policy decisions, and a more humanistic lens is needed to address the trauma and adversity facing these children and their families.

For many of the children we spoke with, the time taken to process visas and the uncertainty this creates for children and their families is at the core of the issues they face. It limits opportunities for their parents to work, deepening the material hardship they experience, it limits their opportunities for play, for hopes and dreams for the future and it places immense strain on the relationships that are central in their lives, all of which are exacerbated by the trauma they have endured and continue to endure.

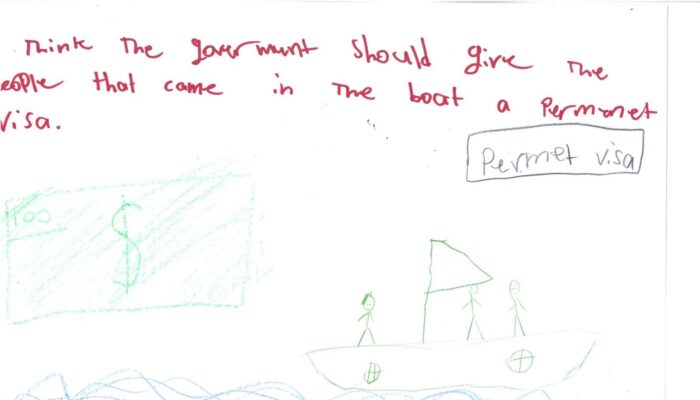

When asked what the government could do to help these children and their families, children spoke of the need to secure a visa, but also better education and healthcare and chances to play soccer. Children were not unrealistic in their expectations or responses, many of which could be considered their basic rights, supporting Sheppard and Von Stein’s (2022) view that Australia’s approach to refugees and asylum seekers is that of a moral issue as opposed to a capacity issue.

Our research is showing that more attention is needed to children, to build child-centred responses so that they and their families can be supported to rebuild their lives in Australia and ensure that no child is left behind. This can only be achieved when we truly listen to children and hear directly about their unique experiences.

References:

Davidson, P., Bradbury, B. and Wong, M., 2023. Poverty in Australia 2023: who is affected.

Lister, R. 2004. Poverty. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Margherita Matera, Tamara Tubakovic, Philomena Murray, Is Australia a Model for the UK? A Critical Assessment of Parallels of Cruelty in Refugee Externalization Policies, Journal of Refugee Studies, Volume 36, Issue 2, June 2023, Pages 271–293, https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fead016

Martin, L., 2023. Budget 2023: What it means for refugees and people seeking asylum. Kaldor Centre for International Refugee Law, May. Available online: Budget 2023: What it means for refugees and people seeking asylum (unsw.edu.au). [accessed 28th November 2023]

Parkinson, M., Howe, J., and Azarias, J., 2023, Review of the Migration System – Final Report 2023, Department of Home Affairs.

Pieloch, K.A., McCullough, M.B. and Marks, A.K., 2016. Resilience of children with refugee statuses: A research review. Canadian Psychology/psychologie canadienne, 57(4), p.330.

Sheppard, J. and von Stein, J., 2022. Attitudes and Action in International Refugee Policy: Evidence from Australia. International Organization, 76(4), pp.929-956.

Treanor, M.C., 2020. Adversity and poverty. In Child Poverty (pp. 159-178). Policy Press