Stuck In The Middle With Whom? What High School Is Like For Refugee-Background Students

THE PROJECT

Moo Dar Eh was a cheeky, softly spoken and facially expressive 15-year-old Karen lass; born and raised in a Thai refugee camp. She had arrived in Australia just over a year prior, which was mostly spent in an intensive English language school. Moo Dar Eh had been recently exited to her local high school – not because her language and academic skills were ready for Year 9 – but because government funding had run out. She was one of seven refugee-background students in my research in which I sought to understand students’ experiences of transition into mainstream secondary schooling, and investigate the factors which facilitated and inhibited transition.

© Amanda Hiorth 2016. All rights reserved.

STUDENTS’ EXPERIENCES OF AUSTRALIAN HIGH SCHOOL

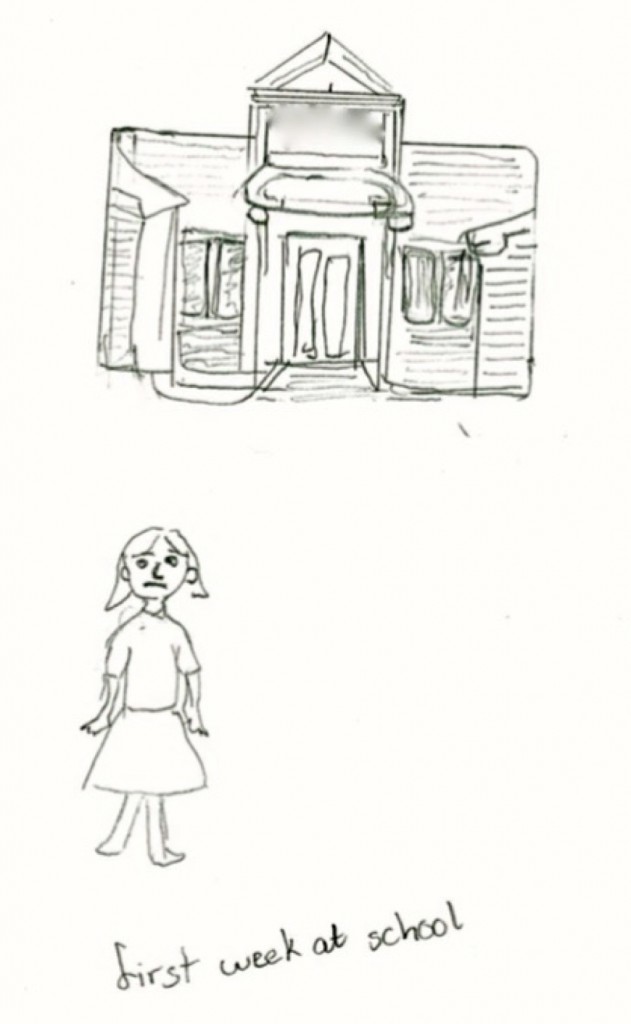

As part of the research, Moo Dar Eh drew me a picture recalling her first day of high school. Although in reality Moo Dar Eh was surrounded by the usual pandemonium of a busy school morning, she had chosen to draw herself as a solitary figure – shoeless, hands wide open, eyes agape. She carried nothing, there was nobody to help her, not even a gate or pathway to enter the intricately drawn school building – almost too austere to enter. It was a stark picture, powerful in its meaning.

When Moo Dar Eh told me about her picture, she remarked: “Butterflies in my stomach. I got lost. I’m not feeling happy, just scared and sad”. Starting high school in the middle of the year was certainly an anxiety-provoking experience, but without a friendly face, with limited English language and without prior experience having studied many subjects in the Australian curriculum it was even more so. The continued sense of failure in class and homework tasks made her feel as if she herself was a failure. It was also true that she was forever getting lost in the humongous school grounds. Her inability to read her detailed timetable meant that getting to class on time was a considerable challenge also, denoting an inability for her to access the most fundamental aspects of schooling. Moo Dar Eh felt lost not only in a logistical sense, but also in a metaphoric sense. She reported feeling deeply alone, that there was nobody to turn to when figuring out how to ‘do’ school, that she was not a real member of the school community. This sudden, culturally shocking beginning to such a new experience of education was one that made Moo Dar Eh withdraw even further into her usually shy demeanor.

TRANSITION – THE BIGGER PICTURE

Overall, the experiences of transition for all students in my research were reflective of Moo Dar Eh’s experiences. I found transition to be a messy and highly complex process for students who have a complex array of needs. Transition is also an individual process – different for each and every student, and a long-term process; one whose parameters cannot be finitely defined in time. The one aspect of transition critical for all students was the social domain of schooling: Without friends, without a support network or contact to approach for help, students were lost in all of its meanings. This lacking social network impacted significantly upon all other aspects of schooling.

WHERE TO FROM HERE?

It’s clear there are many challenges, yet there are as many hidden gems to bridge this tricky transition. English as an Additional Language (EAL) teachers in mainstream schools are incredible advocates for students, connecting them to services, linking families into the education system and continuously fighting battles to prioritise refugee-background students in schools. Mainstream content-area teachers want the best for their students; and, school leadership teams seek to have inclusive and integrated communities where all students can succeed. Students themselves enter mainstream schooling with extraordinary reserves of optimism, resilience, and enthusiasm to learn. Students also bring with them unlimited wealth of resources, skills, abilities and different kinds of knowledge, which, if acknowledged and integrated into classrooms and pedagogy could bring benefits not only for students, but also for the entire school community.

There is much we can build upon – the foundations are already there. What else will help?

- Involving and empowering students to be active agents in their own transition

- Establishing formalized and consistent bridging programmes from English language schools to mainstream schools

- Creating collaborative transition support networks across all segments and institutions of the education system

- Auditing mainstream school practices to fully understand and respond to the needs of its refugee-background students;

- Implementing inclusive, whole-school approaches with culturally responsive pedagogies

- Designating transition specific funding to implement and maintain these recommendations

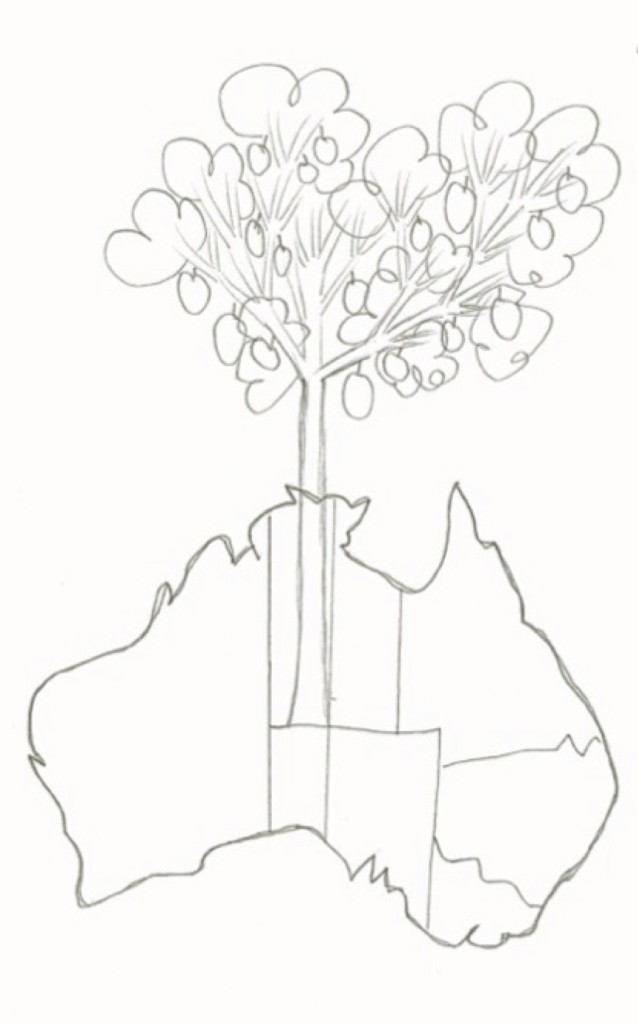

For the students of this study – and their families – education is the pathway to success in society, and a means to ‘give back’ to the country which has provided them with a future of opportunities and possibilities. Yo Shu, another student in this project, drew his hopes for his future in the picture following. In it, he carefully outlined a map of Australia with a tree blooming full of fruit and growing strongly up from the centre. Explaining his drawing, he remarked: “I want to grow my country”. It is these inspiring words which can direct all initiatives towards improving transition outcomes for refugee-background students, and support students such as Moo Dar Eh to feel far less alone and isolated in the education journey.

© Amanda Hiorth 2016. All rights reserved.