Creating Social Cohesion Through a Common Language

Introduction

Positioned at the border between the Middle East and Europe, Turkey has become a country of transit for refugees on their way to the West. As the number of forcibly displaced people continues to increase globally, Turkey hosts more refugees than any other country in the world, including 3.6 million Syrians. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees outlines three paths forward for refugees: voluntary repatriation, resettlement, and local integration.

The continuing civil war in Syria combined with new lives already established in Turkey, make it unlikely that refugees will voluntarily return to Syria. Resettlement to a third country is becoming less of an option as migration policies get stricter. Since 2016 for example, the EU-Turkey Deal on Migration’s “1:1 scheme” exchange policy has reduced the overall number of migrants resettled in Europe. With limited options, many refugees have accepted Turkey as their new home and have begun integrating with the Turkish population.

The EU-Turkey Deal also includes six billion euros of funding for the EU Facility for Refugees in Turkey (FRT). This initiative disburses funds to assorted projects run by international organizations and the Turkish government to support Syrian-Turkish social cohesion. The projects include Turkish language learning programs for both adults and children. According to the European Commission, “Knowledge of Turkish language remains a basic requirement not only for learning purposes, but also as a key factor to support integration, both for Syrian children as well as for their parents and adult family members.”

Definitions and Maps

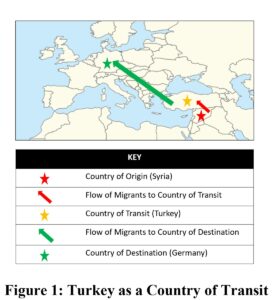

The International Organization for Migration distinguishes between a migrant’s mid-journey country of transit and their end-of-journey country of destination. Figure 1 demonstrates the flow of migrants coming from Syria to Germany and stopping in Turkey as a country of transit.

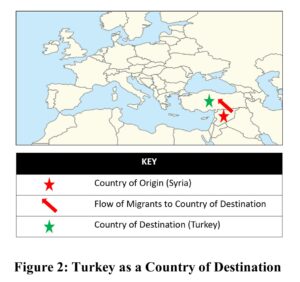

Since “transit” implies impermanence, there is ambiguity regarding the minimum amount of time migrants must remain in a country for its status to shift from “transit” to “destination.” If, for example, a Syrian family fled to Turkey in 2011 and still lives in this “country of transit” ten years later, at what point does Turkey become the family’s destination? Figure 2 demonstrates the flow of migrants coming from Syria, and remaining in Turkey as their country of destination.

Syrians granted Temporary Protection status in Turkey are guaranteed “the right to stay in Turkey until a more permanent solution is found for [their] situation.” Increasingly, the most permanent solution seems to be lengthened residence in Turkey. Turkey’s shift to a country of destination is reflected in Turkish and EU harmonization policies and mechanisms aiming to promote social cohesion between Syrian and Turkish communities.

At the center of social cohesion is communication through a common language; a community cannot truly be cohesive if its members cannot converse with each other. The language barrier is especially difficult in Turkey because the government does not allow public signs written in Arabic. This is partially due to the increased emphasis on maintaining Turkish culture brought about by the influx of Syrian refugees. Additionally, Article 42 of the Turkish Constitution requires foreign language education to be regulated by law. Syrian refugees of all ages can learn Turkish in formal institutions monitored by the Turkish Ministry of National Education (MoNE).

Turkish Language Classes for Adult Syrian Refugees

Adult education in Turkey is governed by the MoNE’s General Directorate of Lifelong Learning. Public Education Centers (PECs) throughout the country provide the main, free option for Turkish language education. Many of the programs at PECs are funded through the EU FRT and implemented by the United Nations Development Programme’s Turkey Resilience Project in Response to the Syria Crisis (TRP). The TRP operates in 53 PECs across ten of Turkey’s 81 provinces, including Istanbul and seven provinces along the Syrian border.

Arabic speakers studying Turkish must start at the beginning with a new alphabet. When the secular Republic of Turkey was founded in 1923, President Mustafa Kemal Atatürk sought to remove Turkey’s historical attachments to the Muslim world and focus on the West. Atatürk’s language reforms replaced the Ottoman Turkish alphabet (based on an Arabic script) with a new Turkish alphabet using an adapted Latin script. The Turkish language was “cleansed” of Arabic and Persian words. These changes were codified in the passage of Law No. 1353, “on the Adoption and Application of the Turkish Alphabet,” which was later incorporated into Article 174 of Turkey’s current constitution.

Integration cannot be one-sided and must involve participation from the host community to be successful. Dr. Maissam Nimer interviewed over 100 stakeholders and found that Syrians report learning Turkish faster while interacting with Turkish friends and neighbors. After the 2016 coup attempt, the Turkish government restricted the activities of civil society organizations (CSOs) including their ability to provide language classes for their beneficiaries. Instead of classes, CSOs are hosting language conversation groups, allowing refugees to practice the Turkish they are learning elsewhere. Dr. Nimer found that language learning activities are more successful when they mutually benefit the Turkish speaker and the Turkish learner. Language exchanges benefit Turks training to become Turkish-as-a-foreign-language instructors and Turks who want to learn Arabic for utilitarian purposes, such as conducting business with the Arab world or practicing Islam.

Integrating Syrian Children into Turkish Public Schools

Three years after Syrian refugees began arriving in Turkey, the Turkish government started addressing the need for Syrian children’s education. Beginning in September 2014, Turkey opened Temporary Education Centers (TECs) inside Syrian refugee camps, which formally taught Syrian children their modified national curriculum. In 2016, the Turkish MoNE started phasing out TECs in favor of enrolling Syrian children in Turkish public schools, thus providing children with additional exposure to the Turkish language and opportunities for social cohesion.

In October 2016, the initial two-year harmonization project was called PICTES: Promoting Integration of Syrian Children into the Turkish Education System. It provided eight additional hours of Turkish language education to Syrian children each week. In 2018, the project continued under a new name, PIKTES: Promoting Integration of Syrian Kids into the Turkish Education System. Implemented in 26 provinces and administered by the MoNE, PIKTES is a country-wide initiative aimed at integrating children with Temporary Protection status into Turkish schools. The program focuses on removing the Turkish language barrier; once Syrian students learn enough Turkish, they can shift their concentration to other academic subjects and social integration.

When Syrian children enroll in a Turkish public school, they take a language proficiency exam. Based on their score, they are placed into an “Adaptation Class” to learn enough Turkish to engage with the lessons in a regular classroom. Once their Turkish has improved, children are moved to a standard classroom with both Syrian and Turkish children.

The success of PIKTES is demonstrated by the continuous increase in enrollment numbers. Program output data shows an overall 32.81% increase in enrollment rates for Turkish public schools and TECs from 2014 to 2019. The total number of Syrian students out of school decreased from 69.58% of the Syrian school-age population in the 2014-2015 school year, to 36.75% in October 2019. Despite the shift to virtual PIKTES programming in March 2020 caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, PIKTES continued its Adaptation Classes remotely; classes were broadcast on Turkish national TV for Syrian children who were unable to access the Internet. Of the 669,630 Syrian students enrolled in school in September 2020 (55.17% of the total school-age population), 404,530 students (60.41%) were enrolled in Turkish language courses. By the end of the 2020-2021 academic year, 750,350 Syrian students (61.81% of the total school-age population) were enrolled in school. With increased student enrollment, both Syrian and Turkish families benefit from the language learning and social cohesion mechanisms provided by PIKTES.

Conclusion

Turkey’s shift from a country of transit to a country of destination is evident from the change in behavior by both the Turkish government and Syrian refugees. While the Turkish government initially viewed Syrians as “guests,” its current educational services do not affirm this view. Government regulated curriculum through PECs and the PIKTES program result in all students learning Turkish to the same standard.

Many Syrians have accepted they will not return to Syria soon if at all. Through CSOs and relationships with Turkish friends and neighbors, Syrian adults are investing in their own Turkish education. With PIKTES-sponsored social cohesion activities for students and parents, Syrians have opportunities to practice what they learn in the classroom. Syrian children are learning Turkish while simultaneously building cross-cultural relationships with their Turkish classmates. Forming such relationships at a young age undoubtedly strengthens social cohesion, ultimately resulting in peace-building.

While the future remains uncertain, it is clear that the Turkish government and Syrian refugees recognize the value of speaking Turkish for social cohesion. As both populations learn to live with each other, they demonstrate the importance of speaking a common language in the maintenance of community-wide peace.