The Model Host: The Global North’s Convenient Guide to the International Refugee Burden-Sharing Regime

This article argues that the ‘model host’ narrative is a Northern tool to further perpetuate unequal distributions of global power within the international refugee ‘burden-sharing’ regime, and that rather than defining the ‘model host’, actors should turn their attention to producing more equitable financial and physical refugee ‘burden-sharing’. The case study of Uganda is used to illustrate this line of argument.

‘Burden-sharing’ refers to how the global responsibility for refugee protection is achieved – comprising of both financial costs and physical hosting. However, there are no legally binding commitments to global burden-sharing – only normative statements: most prominently, the preamble of the 1951 Refugee Convention states that “the granting of asylum may place unduly heavy burden on certain countries, and a satisfactory solution cannot therefore be achieved without international cooperation”.

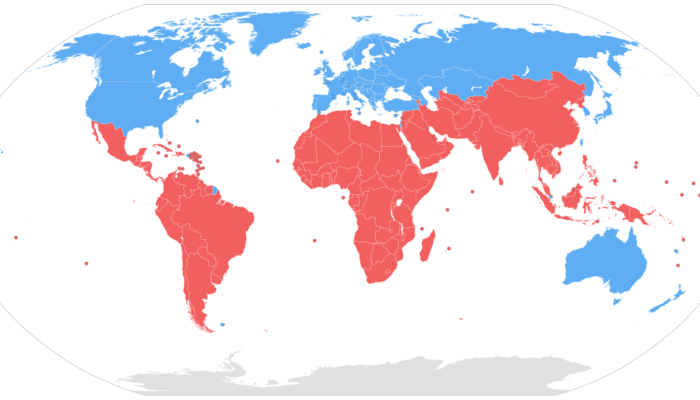

Such international cooperation is, of course, subject to the perverse distribution of global power – particularly the North-South power divide. Global refugee data supports such an assertion: 85% of global refugees are hosted in ‘developing’ countries. What’s more, whilst richer countries often proclaim that they contribute financially, rather than physically, their monetary contributions continue to fall short. For instance, as Bursalioğlu noted [pdf], between 2012 and 2016, the Turkish government spent over 10 billion USD in order to host millions of refugees fleeing the Syrian Civil War, but international support totalled just 445 million USD. Consequently, host nations are forced to spend large portions of their budgets providing refugees with basic necessities, and local host communities experience increased labour market competition, over-run public services, and increased prices for food and rent.

The heavy influence of power dynamics within international ‘burden-sharing’ is not a new observation, and it has been widely discussed within refugee studies scholarship. However, the Northern idea of a ‘model host’ as a tool to perpetuate such dynamics is yet to be explored. Uganda is often cited as a model host by Northern governments, policymakers, and NGOs. Refugees who flee to Uganda benefit from the nation’s open-door policy, the right to work, freedom of movement, and equal access to public services such as hospitals and schools. They also receive a plot of land that can be used to grow food or operate a small business. There are now approximately 1.4 million refugees hosted in Uganda, primarily from South Sudan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Advocates for Uganda’s progressive refugee policies argue that by facilitating the assimilation of refugees, hosts such as Uganda can produce a ‘win-win’ scenario, whereby refugees enjoy a larger range of freedoms, and host communities benefit from the expansion of the labour force, and regional development as a result of the international aid and domestic spending which accompany refugee movements. Thus, it is argued that the negative consequences experienced in host communities are actually the result of their own faulty refugee policies which fail to utilize the skills of refugees (and not because of a dysfunctional international ‘burden-sharing’ system).

However, claims of a ‘win-win’ scenario between refugees and host communities in Uganda fail to account for the declining capacity of Uganda’s host districts. This is particularly true for so-called ‘unskilled’ labourers such as agriculture and seasonal construction workers: refugees are willing to work for lower wages, and therefore saturate labour markets. Thus, landlords and business owners enjoy a new, cheaper source of labour, whilst the poorer individuals find themselves with reduced job security, and local-level inequalities are perpetuated [pdf].

What’s more, the ‘model host’ title overlooks the increasing difficulty that Uganda is having in upholding its progressive policies: the plot of land afforded to refugees has gradually reduced since 2016 from 50x50m down to 30x30m, an area which refugees claim is insufficient for subsistence farming. As a result, land disputes between refugees and local people are becoming increasingly common. Disputes have also arisen regarding competition for natural resources such as water and firewood, with women claiming they spend the majority of their time queuing to obtain these basic necessities. This is particularly damning because conflicts across Africa are becoming increasingly protracted, leaving thousands, and in some cases millions, of refugees relying upon the capacity and resources of their host country for years or decades.

Consequently, pointing to certain benefits which are enjoyed by certain members of the host community overlooks what is, in reality, an extremely complex situation, which will vary over time and most likely provide the worst outcomes to those already suffering from some form of marginalization. The aforementioned assertion of the model host is therefore an extreme simplification, and one which conveniently shifts the blame from the Northern states who are failing to act either financially or physically, to poorer host communities who are already struggling to meet the needs of their own populations. In the end, it is the refugees, and marginalized hosts, who suffer from the negligence of the most powerful actors. To ensure the human rights of these groups are upheld, global justice within the international burden-sharing regime is vital.