The EU’s Relocation of Unaccompanied Migrant Children to Safe Havens: A Good Practice?

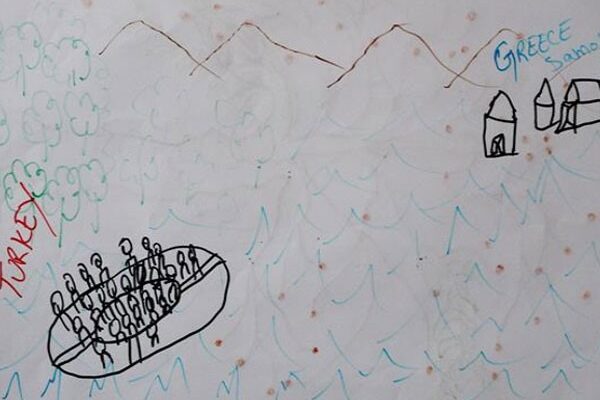

The COVID-19 pandemic as a ‘ticking health bomb’ has proven to be a difficult time for everyone, but for the Unaccompanied or Separated Migrant Children (UAMCs) stranded on the Greek islands, certain opportunities have emerged.

The urgency caused by the pandemic coupled with the campaign ‘Free the Children’ by Human Rights Watch has compelled the European Union (EU) to establish a plan to relocate 1600 UAMCs from the Greek island to safer states. The campaign highlights the precarious condition of Greek hotspots / first reception facilities that were established for the initial reception, identification, registration, and finger-printing of asylum-seekers arriving through sea. These reception and identification centres were established in Greece and Italy after the 2015 refugee crisis with an aim to regulate irregular migration.

The relocation scheme is a part of the provisional measures mandated through Article 78(3) of the Treaty of the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) [pdf] in emergency migratory situations. Such provisional measures have been adopted by EU in the 2015 refugee crisis. In its first phase of the scheme, Luxembourg successfully relocated 12 UAMCs on 15 April, 2020 which was then followed by Germany.

Greece, as a gateway to the EU, is both a transit and recipient state and receives almost two-thirds of its asylum-seekers as women and children. This category is one of the most persecuted and is frequently exposed to severe risk of exploitation and generalized violence. In Greece, it is governed under the Law 4554/2018 that lays down the guidelines for the custody or guardianship of UAMCs. Unfortunately, most EU states do not have specific laws concerning the rights of UAMCs. With the exception of Belgium, most states rely on the interpretation of their domestic laws on asylum in consonance with their obligations set out in the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) to advance protection to UAMCs. Belgium took a series of steps in enacting specific laws including the UAM Guardianship Law 2002 after the European Court of Justice in Mubilanzila Mayeka v. Belgium reprimanded it for detaining a five-year old girl for two months in a detention centre designed for adults. The court observed that such practice is a proof of ‘a lack of humanity and constitutes degrading treatment’.

The Qualification Directive 2011/95/EU sets international protection for asylum-seekers in EU including the grant of refugee status. Article 2(l) of the Directive defines a UAMC as below the age of 18 years who is unaccompanied by an adult responsible to ‘effectively’ take care of his or her protection. The Directive requires a state to extend appropriate care and custodial arrangements to UAMCs. The Directive duly recognises the ‘best interest’ principle of the child laid down in the CRC that necessitates that member-states ensure well-being, social development, family unity, and security as its primary responsibilities. Further, the General Comment No.6 on the Treatment of UAMCs outside their Country of Origin denotes that a state is also responsible to consider factors such as the nationality, identity, cultural and linguistic background, and other special protection needs of UAMCs while ensuring their rights.

Article 24 of Directive 2013/32/EU on reception standards read alongside Article 18.2 and 20.1 of the CRC puts a specific obligation on Greece while assessing the asylum application of a UAMC. This includes the appointment of a guardian in addition to a legal representative for assisting a UAMC during the assessment procedure including the personal interview. The guardian is responsible to explain the procedure of personal interviews as well as their repercussions and the assessment must be done in a friendly environment with qualified and trained professionals in child rights.

Despite the international law prescribing for special protection needs, Greece has been detaining UAMCs under the euphemistic category of ‘protective custody’ and on the basis of pre-removal or ‘asylum detention provisions’. While UAMCs should be subjected to a ‘safe referral to appropriate accommodation facilities’ [pdf] and not held under asylum detention provision for a period exceeding 25 days, in protective custody [pdf] there is no restriction on the time period. This remains the stagnant approach of Greece despite receiving hefty funds of two-billion pounds from EU aid.

UAMCs as per Article 11.3 of the Directive 2013/32/EU cannot be detained in any situation as it is inconsistent with the best interest principle. This also amounts to torture and degrading treatment under Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights [pdf] and Article 20 of the CRC as observed in Sh.D. and Others v. Greece. Moreover, the 2019 UN Study on Children deprived of Liberty observed that detention cannot be considered even as a last resort or in the best interest of the child as it exposes them to psychological and mental disorder, sexual abuse, and hampers their growth.

In 2017, Greece pledged to not detain UAMCs anymore. However, cases such as UAMCs being held in arbitrary detention for a considerable period in police cells, intentionally identified as adults, and placed with unrelated adults due to the unavailability of shelters have emerged. These measures are in violation of Article 11 of the Directive 2013/32/EU.

The treatment of UAMCs around the world is concerning. While in Paris, some are forced to sleep on roads, others are held at the Mexico-US border waiting for their forceful deportation. The relocation scheme is a sustainable short-term solution, but the issue calls out for long-term harmonised protection standards. Undoubtedly, some states are over-burdened than the rest, especially because of the Dublin II Regulations. The Dublin Regulations, as a part of the Common European Asylum System, require that the state where an asylum seeker-first entered the EU take responsibility for assessing the claim of asylum. The situation calls out for more equitable burden-sharing methods by addressing international responsibility and establishing a tripartite system of partnership with EU member-states, international organisations, and third states outside EU. This system would speed the process of family tracing and reunification. All of this should be pursued with an aim to effectively implement the best interest of child.