Refugee crisis: the immediate and lasting impacts of powerful images

Emma Thomas, Associate professor, Flinders University; Craig McGarty, Professor, Western Sydney University, and Laura G. E. Smith, Senior Lecturer in Social Psychology, University of Bath

This article is about the power of emotive images to create social and political change. However, we have chosen not to display distressing images, including those of Aylan Kurdi, for ethical reasons.

Recent images and footage of migrant children housed in wire cages near the United States’ southern border have fuelled global outrage.

President Donald Trump has now signed an executive order to end the separation of immigrant families at the US-Mexico border. Trump apparently bent to public pressure from many sides, including the feelings of his wife Melania Trump.

But apart from driving policy in the short term, do confronting images create change in public perception and willingness to act in relation to refugee issues?

We recently published three papers looking at the psychological impact of refugee images on the public. Our findings suggest that Facebook and Twitter can act as the engine room for public engagement with refugees. Online interactions allow people to move beyond thinking of the refugee crisis as something “they should do something about” to something “we will take action on”.

The little boy on the beach

On September 2, 2015, the world was confronted with distressing images of three-year-old Syrian refugee Aylan Kurdi, who drowned while trying to reach safety off the coast of Turkey. The pictures were rapidly disseminated through the global and social media – within 12 hours of publication, they had reached almost 20 million people.

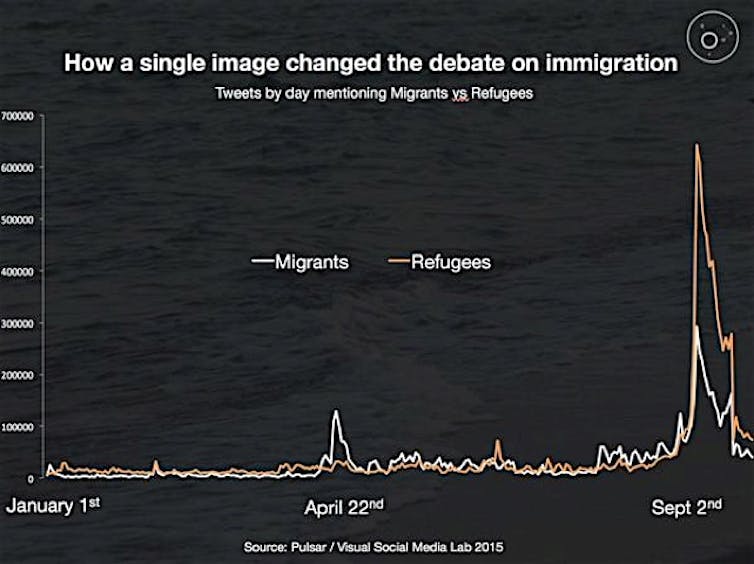

Visual Social Media Lab, CC BY-NC-ND

Like the other 20 million people, we first saw those gut-wrenching images in our Facebook and Twitter feeds. But we also noticed something else about the images: they seemed to be provoking interaction and engagement among people who would not normally be moved to discuss the refugee crisis.

Within days, the government of Australia – a nation where both “sides” of politics have, over the years, maintained thousands of asylum seekers in offshore detention – bowed to the public pressure generated by the image.

The Australian government announced an increased refugee intake of 12,000 Syrian refugees and pledged A$220 million in support.

But the response was personal as well as political: World Vision Australia reported a 3,000% increase in donations, a trend that was echoed globally.

There was something about that image that motivated people, seemingly everywhere, to engage with the plight of refugees. Why?

If, as is commonly assumed, social media engagement is just pointless chatter, how did the responses of many thousands of individuals online add up to effect those dramatic global and social changes?

To find answers to these questions, we conducted three studies that assessed the psychological impact of the images.

Feel, think and connect with others

The images were deeply emotive, and we know that emotions are strong drivers of actions to (attempt to) change the world. Similarly, the images provoked public discussion about “who we are” as a people. Much of the discussion – online and politically – focused on how to support refugees effectively.

Consistent with these observations, psychological science recognises that there are three primary drivers of action to bring about social change. These relate to the emotional experiences one has about the injustice; one’s sense of who one is (identity); and one’s beliefs about the effectiveness of acting together.

Because the response to Aylan’s photo was global, and social media transcends national borders, we surveyed people in six different countries (Hungary, Romania, Germany, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Australia). We tested whether the impacts of the image were the same across nations, or whether different “local” realities came into play.

We gave each participant in our research US$1, for them to allocate either to support Syrian refugees or disadvantaged children in their home country. We looked at how our measures explained where people chose to donate that money.

Our results confirmed that, in those different countries, exposure to the image through social media effectively created a powerful constellation of those three psychological factors.

Exposure to the image was associated with increased emotions – feelings of sympathy for refugees, and guilt about doing nothing. It was linked with changes in a sense of identity: “we are” people who support refugees.

And interactions about the image also helped promote the belief that together “we can” successfully address this state of affairs.

It was this cluster of factors that strongly predicted past action (action already taken to support refugees) and intended future action to donate, or contact a politician. Tellingly, the same factors predicted the allocation of more actual money to support refugees, although the link was slightly weaker in Romania than the other countries.

Compassion (fatigue) begins on Twitter

Our findings above suggested that the images were powerful because they provided the motivation to act, but social media also provided the means of exposure, as well as a way to share ideas and coordinate actions.

This raises the question: what happens when those interactions fade away?

In a separate study, we examined what happened to the same set of factors (emotions, identity, beliefs) when discussion about the image on social media subsided over time. We compared the responses of the same group of people sampled in the immediate aftermath of the images (September 2015), and surveyed them again one year later.

The results were disheartening for refugee advocates. As the frequency of discussion about the image and refugees subsided in social media, that same cluster of factors (relating to identity, emotions and beliefs) also reduced. And it was the reductions in those levels of emotion, identity, and beliefs about acting, which explained decreased support for refugees one year later.

Changes over time

This needn’t always be the case though.

In a final study, we analysed tweets about Aylan Kurdi and the refugee crisis. Specifically, we looked at more than 40,000 tweets posted a week before the images of Aylan Kurdi emerged, during the week they emerged, and 10 weeks later (which was also the time of the Paris terror attacks, 13th November 2015).

We created an index of support for refugees from the words (content) of the tweets, and modelled how support changed over time.

Again, contrary to suggestions that online interactions are fickle, our analysis showed that support for refugees can be sustained over time (even in the context of heightened fear of terror attacks) if people continue to discuss the plight of refugees, and the harm and threat they experience when attempting to seek refuge.

In combination, these results suggest that powerful images, like those of Aylan Kurdi, can have an immediate and lasting impact on people as individuals, but also as members of societies.

The findings also refute suggestions that online interactions about emotive topics are trivial or superficial. Rather, our results suggest that part of the key to sustaining support in the longer term hinges on maintaining levels of popular and political discussion about these events.

Interacting on social media is no magic wand to end suffering, but it is one way for people to “become the change that they wish to see in the world”.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.