Book Review: Acts of Cruelty – Aileen Crowe

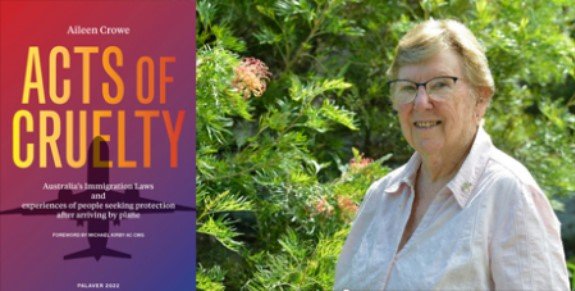

“Acts of Cruelty: Australia’s Immigration Laws and experiences of people seeking protection after arriving by plane”, Aileen Crowe, Palaver, an imprint of Ethica Projects Pty Ltd, 2022, 228 pages

Franciscan nun Aileen Crowe PhD is one of Michelle Peterie’s visitors to Australian onshore detention centres, with her decades of work for marginalised people in Australia and Papua New Guinea enabling a gritty and grounded view and an aversion towards depersonalised legal jargon. She has seen enough of this already: the compliance officers who pin their nametags to the hem of their shirts, so their high office counters make it difficult to identify them in a complaint, and the correspondence signed with a number rather than a name, requiring a response to “Dear 603284.” The many individuals and families she came to know and represent came by plane with valid visas, often approaching her as a last resort, at the sharp end of legal decisions. She found their cultural disorientation often brought on physical, psychological, and emotional trauma, and decided to research the way cruelty was endemic in government decision-making; the result is a PhD and this book.

The early chapters allow us to “walk beside” her refugee friends, learning of their country background and basis for protection claims, with later chapters documenting the bureaucratic process, appeals and interactions, and the judicial, parliamentary and ministerial “god powers” (she has made over 50 appeals to seven different ministers). This is a deep dive into their daily lives and views, not confined to the legalities, but also their births, weddings, funerals, the seemingly endless forms for Centrelink and schools, CVs for job applications, references, traffic infringements and court appearances, hospital visits, tutoring, and babysitting. This close involvement provides the basis for her conclusions about what it’s like to deal with a “toxic immigration culture sanctioned by parliament, a culture that allows systemic cruelty to operate”. While the names of her friends are changed, she does not shirk from providing detailed comments on particular decision-makers and their false assumptions and consequential errors, misinterpretations or negative approaches to decisions of great moment, possibly due to slippery notions of how to assess the refugee’s credibility. An emerging issue here is the politicisation of appointments by the Morrison government to the relevant legal adjudication bodies, currently being investigated for its influence on decision-making. She sees the growing authoritarianism of government as expanding the domestic borders of its sovereign power as well as its sovereign border protection.

No stone is left unturned by Aileen Crowe: her research extends from the ‘micro’ to the ’macro’ situation, examining the UN’s role, Australia’s racist White Australia and Indigenous past, and more broadly to integrate feminist, professional, academic and community activist perspectives. Crowe is inspired by feminist R K Bergen’s advocacy of “passionate scholarship” where “researchers are allied with those being studied, and work with great devotion to eliminate oppressive social structures”, listing many well-known Australian women who have been with her on the journey. The book includes a useful Glossary, and an Appendix providing the visa history of the 10 people/couples researched, as well as a diagram of the processes and available choices. It has a valuable Foreword from Michael Kirby, connecting Crowe’s experience with his own, as a former High Court Justice closely involved in decisions about refugee and social justice issues.

Kevin Bain’s refugee reading guide is at Bayside Refugee Support.