‘Boat people’ and borders: changing political debate on asylum seekers

Since the arrival of the first Vietnamese refugees in the mid-1970s, Australia has maintained a curious fascination with ‘boat people’. Just under 70,000 people have sought asylum in Australia in this way since 1976. By comparison, over the ten-year period to 2015, Australia welcomed more than 80,000 recognised refugees, more than one million permanent migrants, and hosted at least 2.5 million temporary migrants. To compare budgetary investments, in 2015 a $3.05 billion contract was awarded to Transfield to run offshore processing centres in Nauru and Manus Island for the detention of a few thousand people, compared with just $264 million in the 2016-17 Federal Budget for settlement services and English language programs for other migrants.

How could a relatively small number of ‘boat people’ warrant such a disproportionate investment of public resources? Research I have conducted with Liam Magee and Shanthi Robertson from Western Sydney University has examined how Australian politicians have played a role in shaping the public discourse on boats and asylum seekers over the years.

We looked at transcripts from the parliamentary record over three periods: 1977-79, 1999-2001, and 2011-13. These were significant timeframes in the evolution of Australia’s policy towards boat arrivals, correlated with dramatic events (like the MV Tampa incident in 2001) covered extensively in the national media. Federal elections in 1977, 2001 and 2013 also sharpened public debates on immigration. We analysed parliamentary language co-located around use of the term ‘boat people’ in these periods to examine their treatment in policy debates.

We found that, with increasing usage of the term ‘boat people’ over each period, the debate has shifted from humanitarian and pragmatic concerns towards securing borders, dealing with ‘crime’ and managing logistics. These shifts reflect global trends in how nation-states address fears about unplanned immigration. Governments reassert territorial borders through physical ‘spectacles’—establishing detention centres, employing border security agents, conducting raids and deportations, and so on. But language is also a critical tool in doing ‘border work’, with changes in official language signifying changed policy priorities.

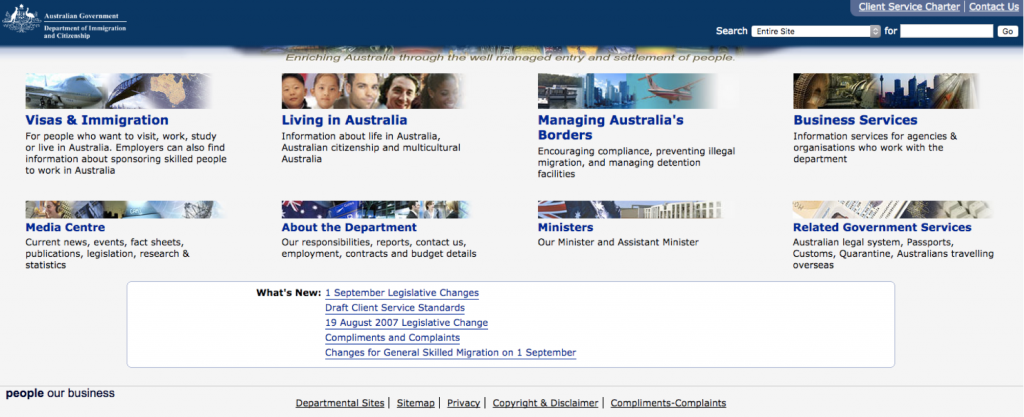

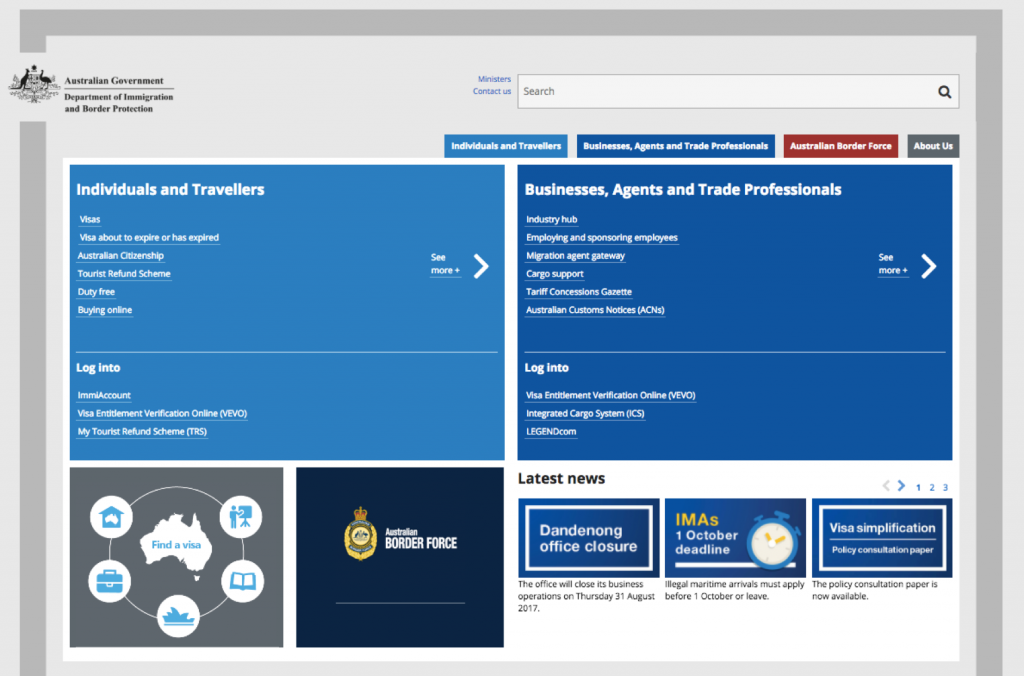

As an illustration of this shift, the former Department of Immigration and Citizenship website in August 2007 (Figure 1 below) included images of people and the refrain ‘enriching Australia through the well managed entry and settlement of people’. In contrast, the current Department of Immigration and Border Protection website (Figure 2 below) has no such mission statement, no images or references to ‘people’, strong ‘borders’ around text, and a ticking clock for ‘illegal maritime arrivals’ who must apply for a visa. The focus of the Immigration Department has clearly changed over this ten-year period.

Figure 1: The former Department of Immigration and Citizenship website in August 2007

Figure 2: The current Department of Immigration and Border Protection website

Turning to the findings of our study, parliamentarians in the 1970s were more likely to use the term ‘boat people’ synonymously with ‘refugees’. Debates were typically focused on achieving clarity on the precise numbers of arrivals and how they would be accommodated in Australia. Perhaps owing to the well-known political situation in countries like Vietnam, there appears to have been little dispute of the validity of ‘boat people’s’ asylum claims.

From 1999 onwards, parliamentarians began to criminalise ‘boat people’–the frequency of terms such as ‘illegal’, ‘smuggling’, and ‘detention’ increases. With the debate shifting to border protection, other phrases which we now recognise as common to asylum seeker debates emerged: ‘playing by the rules’, ‘sneaking through the system’, ‘jumping the queue’, and ‘exploiting loopholes’. This discursive shift represents a (re)construction of ‘boat people’, not as originating from war or political upheaval in other countries, but as the product of supposedly ‘sophisticated’ commercial people-smuggling operations, thus casting suspicion on the legitimacy of those seeking humanitarian protection in Australia.

Finally, as asylum seeker debates reached a fever pitch amidst record numbers of arrivals between 2011-13, the federal government is judged by its effectiveness in making Australia’s borders more ‘secure’ for our ‘protection’. The increased frequency of terms like ‘tax’, ‘deal’, ‘pay’ and ‘budget’ demonstrate attention to the government’s perceived (mis)management of the boats issue, and the turn towards investment in bureaucratic ‘solutions’ to address it. The debate also becomes more partisan, with ‘boat people’ used by speakers alongside party names (not a feature of earlier years) to directly confront and attack their political adversaries.

When speaking publically, politicians use carefully-chosen words to offer their particular versions of reality. Migration, however, is a complex phenomenon, and its consequences are not easily managed. In September 2017, the Federal Government was ordered to pay $70 million in compensation to nearly 2,000 former detainees of Manus Island, rather than see a lengthy class action proceed in court—representing what could be the largest human rights payout in Australia’s history. Terms notably absent from years of parliamentary debates–like ‘ethics’, ‘care’, ‘reception’, ‘partnerships’, ‘collaboration’, or ‘transparency’–could have paved the way for more effective and humane alternatives. A narrow framing of policy issues thus leads to a poverty of effective options for governments, which can backfire spectacularly.

Postscript: This blog is based on the contents of a draft paper by the authors, currently awaiting peer review.