Reflections on Refugee Backlash and Gendered Harms

Within a window of 15 hours, I virtually travelled in time zones from GMT -5 to GMT +5. These journeys reminded me yet again about some of the most haunting downfalls of humanity.

First, I participated in the Bold New Voices in Migration Research Conference organised by the Immigration Initiative at Harvard and Perry House. Sarah Mardini and Salaam Aldeen, in their keynotes, highlighted the ever-increasing hardship refugees and activists continue to face. Fleeing wars and saving lives, many instead of refuge encounter penalisations in their countries of destination. For example, some face charges for smuggling and trafficking during rescue operations in the perilous sea crossings.

In another keynote reporting on the border crisis and femicide, Alice Driver stressed the appalling sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) against unaccompanied minor migrants at the Mexico-US Border. Many migrant girls have been subjected to sexual violence and the lives of some exchanged to settle disputes between different groups. The space for journalists eager to document the violations has been shrinking, too, with additional state controls.

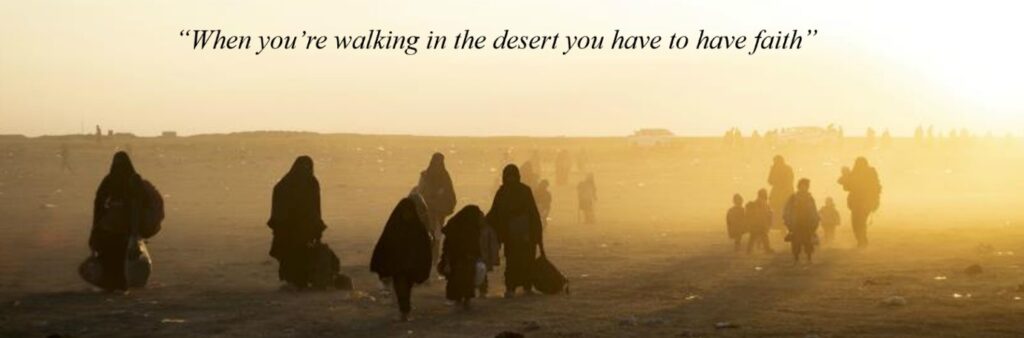

In the panel on Intersecting Identities, my talk on “Rethinking Resilience: Adapted Religious Coping among Forced Migrant Women Survivors of SGBV” presented the functions and impacts of religion on refugee women’s coping and mental health. I introduced how SGBV increases with the length of forced migration and how survivors, often without support, draw inner strength from their intersecting identities. Religion, as an integral part of one’s identity among the majority population, emerged in my study as a primary source of coping capacities in displacement.

Quote-Ghanaian asylum-seeking woman in Tunisia (in Pertek, 2021). Photo-Getty Images

I called for an intersectional ecological approach to resilience to recognise the social location, context and structures affecting one’s psychological distress levels and coping behaviours. Mental health supports might consider, and build upon, forced migrant inherent coping strategies, such as religious coping, where prevalent. To enable displaced populations to deploy their known ways of coping, access to relevant resources needs to be facilitated.

Second, twelve hours later, I met with Cox’s Bazar’s MHPSS Working Group to share some transferable findings from my research with Levantine refugees in Turkey and Sub-Saharan forced migrants in Tunisia. I was saddened to hear about the impact of recent fires in the world’s largest refugee camp, sheltering more than 600,000 people, including many Rohingya SGBV survivors. Particularly worrying is the rising suicidal ideation in the camp.

Third, in the meantime, I have also been following the migrant situation in Tunisia and the difficulties some refugee SGBV survivors face as they await resettlement. Inaccurate information and sometimes misleading resettlement prospects deteriorate psychological distress and compound traumas in the survivors’ post-Libya experiences. Some in desperation consider leaving for Europe again despite life-threatening risks in the Central Mediterranean route. Sea arrivals continue, so the number of missing migrants grows daily. The resettlement needs surpass the resettlement places offered by receiving countries.

An incremental refugee backlash, suggested by recent events, continued anti-immigrant sentiments and still insufficient solidarity (leading to a continued migrant death toll) take me to questions I posed as a child. I often wondered, reflecting on WWII and my grandma survivor’s stories: how could so many people die when the world was watching? As I lived near and visited multiple times one of the most brutal Holocaust concentration camps, I questioned, “Did people not know?”.

History repeats itself — wars are widespread. 80 million forcibly displaced people seek refuge. Many suffer from high levels of interpersonal and structural violence. Sadly, the post-Covid-19 world tightens borders, forcing people to take even more dangerous pathways for their survival.

Yet, today, as we witness some of the dark times, I know the answer to my earlier questions.

And there is one Czesław Niemen song, that I have continued to chime since a young age, providing some answers and emanating hope as “good wins over evil”:

“Strange is this world,

where still is

so much evil.

And strange is the fact that

for so many years

man has been scorning man.

This strange world,

the world of human affairs,

sometimes it is even such a shame to admit it.

But it is often like this

that someone kills

with an evil word as if with a knife.

But there are more people of good will

and I do strongly believe in the fact

that this world

won’t never die due to them.

No! No! No!

The time has come,

it’s high time

to destroy the hatred within.”

Lyrics source: https://www.lyrtran.com/Dziwny-jest-ten-swiat-id-176110