Can Opposing Groups Agree To Disagree?

How many migrants should we take? Is our border protection adequate? Are detention centres warranted? Australian society continues to be fragmented in attitudes towards these pressing issues. But is there a way to encourage civil discussion between opposing groups?

The world is facing a migration crisis, with a record 69 million people displaced worldwide. Ironically, Australia’s migrant intake is at its lowest in the last decade. Members of political parties express divergent opinions on approaches to handling this crisis. But it’s not just our political leaders who are polarised on migration. The general public is also becoming more polarised in their political beliefs.

Online platforms exacerbate this political polarisation, by providing accessible outlets for people to advocate for their positions on socio-political issues. However, moderating polarised attitudes is important to encourage cooperation between different groups. Unfortunately, traditional attempts to moderate polarised attitudes (e.g. persuasive advertisements) tend to be unsuccessful, especially when advocates are highly convicted in their viewpoint.

This begs the question, can we encourage political advocates to become more open to opposing viewpoints?

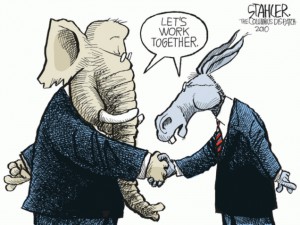

Illustrated by Jeff Stahler in the Columbus Dispatch

Encouraging opposing groups to cooperate seems like an ambitious task. But the first step in achieving this goal is to understand the intriguing psychological processes underlying advocacy. That is, what happens behind the scenes when people advocate for their own opinions? We are not interested in whether advocators succeed at convincing their audience. Rather, we are interested in whether advocators can somehow end up convincing themselves.

People can persuade themselves

Myself and Dr. Simon Laham at the Melbourne School of Psychological Sciences speculate that people can persuade themselves when they try to persuade others.

We can all relate to this idea, given the recent same-sex marriage referendum in Australia. This issue involved classic polar opposites – a Yes, No question. People who were highly convicted on either side of the debate, the more they spoke about their attitude in attempt to persuade others, the more they persuaded themselves. This is called self-persuasion. Indeed, previous work in this area shows that people’s attitudes tend to become more extreme when they talk about them.

But what if we tell you that sometimes, people’s attitudes can actually become less extreme, even after advocating for them? If we uncover the specific processes underlying self-persuasion, we can find ways to encourage people to question their own attitudes towards migration. What this means is that polar extremes do not need to stay there – we can bring opposing groups closer together.

When advocates realise holes in their own arguments

To pilot test our theory of advocacy and self-persuasion, we asked a group of college students to advocate online for their position towards a carbon emissions policy. We did this to mirror the ways in which people typically advocate in contemporary society – online commenting on Facebook or Reddit.

Once the advocates advocated for their position, we prompted them to think about the arguments that they generated. Interestingly, those who realized that some of their arguments were flawed, ended up questioning their own attitude. This occurred regardless of which stance the advocates took initially. For example, it did not matter whether advocates were initially for or against the issue, they still questioned their own attitude.

Where to now?

Of course, much more is to be discovered. The next step forward would be to test advocacy and self-persuasion in the context of migration. Can we stimulate civil discussion between Anti and Pro migrant advocates by encouraging each group to question their own opinions? Future experimental work is required to demonstrate the strength of self-persuasion effects and its further consequences. Nevertheless, we provide the first evidence to suggest that people can positively persuade themselves and come closer to someone who disagrees with them on a pressing issue of the 21st century.

The need for this cooperation clear in the context of migration. What we need is for people on either side to cooperate in designing effective solutions to new issues that may arise. Groups with different perspectives need to cooperate, rather than continue to fight. Opposing ideologies need to agree to disagree – and our work suggests that this is possible.

Imagine a world where it is possible to encourage social harmony, all the while retaining the right to free speech. A world where we could be open to someone else’s opinion without necessarily changing our own. THIS is the pluralistic Australian society we should continue to envision.

1 Response

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Pingback : Regional Focus: Australia – AnAttorney.com